There have been plenty of discussions in Canada’s security and emergency management spaces recently, stemming from conversations about using the Canadian Armed Forces as a domestic disaster response agency. Does Canada need an emergency management agency?

There have been plenty of discussions in Canada’s security and emergency management spaces recently, stemming from conversations about using the Canadian Armed Forces as a domestic disaster response agency.

I’m writing this post in direct response to a recent CBC piece: Does Canada need a national emergency response agency? While the article highlights this issue that has been studied immensely, the title really should be: Does Canada need an emergency management agency?

The answer is yes. (In my opinion, of course.)

Stick with me—this is going to be an essay-length post. I’m going to discuss why Canada needs a FEMA-like agency/organization, what it would look like, and the next steps in the evolution of disaster preparedness, response, and recovery in Canada despite our jurisdictional challenges. We’ll also look at some of the purported downsides to this structure.

Part I: Why Canada must evolve to centralize emergency management through a FEMA-like organization

In Canada, all emergency responses start locally before turning to provincial and federal authorities. And yes, this means that each step in the process requires a level of bureaucracy to request assistance—very few actions are automatic.

The last few years have shown us the limits of this approach.

It started with COVID-19. Then, we saw significant fires that burned down communities. Then floods. Then, an ideologically driven extremist meetup shut down the nation’s capital and many major border crossings for weeks. Then, of course, the worst wildfire season on record. And, of course, these are just the emergencies that make it to the national level that we all know about. The federal hub of EM, Public Safety Canada’s Government Operations Centre, is notorious for its budget constraints, staff turnover, and legacy infrastructure.

Lost in the mix are the First Nations that still lack clean drinking water, infrastructure issues plaguing major cities, and local incidents that probably need more oversight from experienced professionals with more resources.

From the outside, all of the events above have been… managed. I’ve assisted in managing some of them in my various roles. But I (and many others) see the limits of our current approach.

Here in Canada, we have a unique qualm about respecting provincial authorities, even when we probably shouldn’t—or rather, we should shift authority (e.g., EM, policing, and healthcare). Instead, we motivate each local region to respond to an event on its own first, and then we expand the authorities and responsibilities depending on the consequences.

However, when an incident reaches a level where coordination between jurisdictions is crucial, we are already starting on the back foot by requesting assistance from the next jurisdiction. We often see these jurisdictional issues more clear during criminal events (such as the 2022 Freedom Convoy and associated border blockades), where it is unclear between multiple police forces (in the case of the convoy, the OPS, the OPP, the RCMP, the PPS, the SPVG, the SQ) who holds responsibility. However, the same jurisdictional problems can arise when a weather event crosses regional/provincial boundaries, when critical infrastructure in one region fails, causing issues for a neighbouring area, and much more.

By centralizing authorities and aligning resources to a single entity (while allowing provinces and local municipalities to retain their EM staff), we can better coordinate preparedness efforts and mitigation measures while ensuring the right individuals are on the ground and in the office (EOC) to respond to events.

Part II: Illustrating the possible structure within the Canadian ecosystem

This would be the time when I would show the current state and proposed end states (in graphic flowchart form) of the Canadian EM system… but it’s a mess.

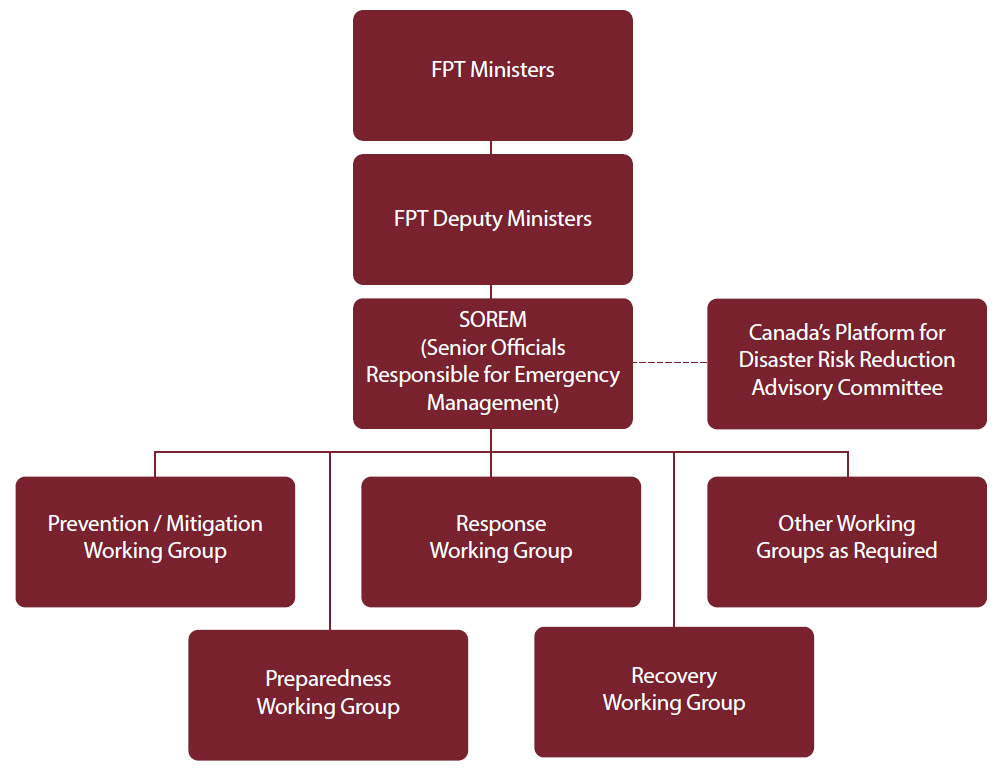

First, we have the level of governance from all political leaders, which from the EM Framework for Canada looks like this (FPT = Federal, Provincial, Territorial):

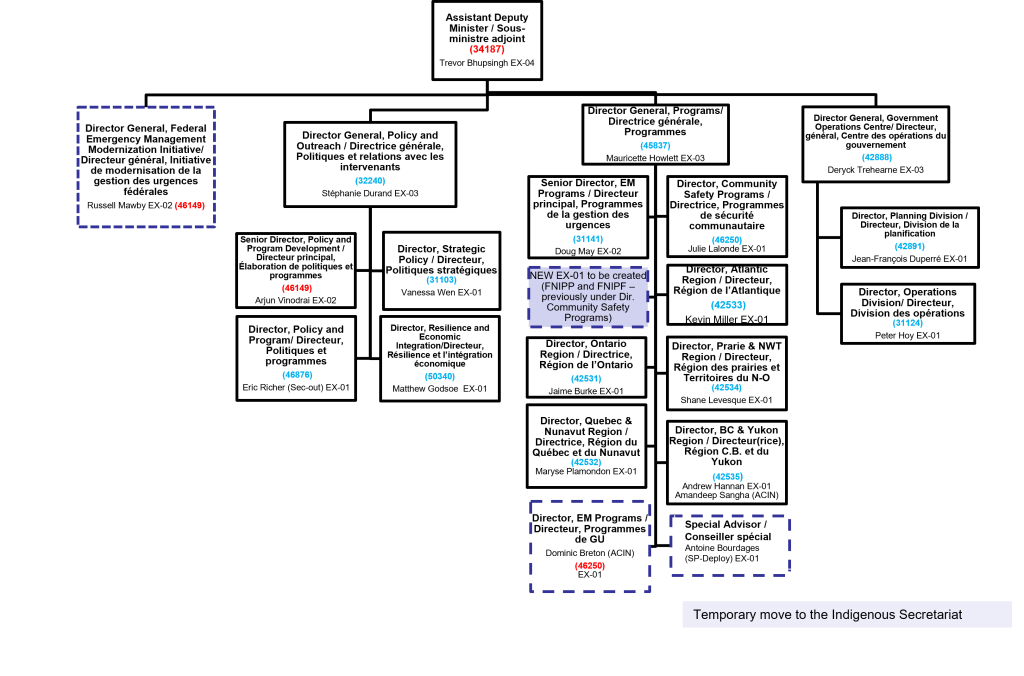

Next, we have the governance for EM at the federal level:

And then, well, we have each federal department that could have a primary role; there are over a dozen (emergency) operation centres within the federal government alone (Public Safety, CSIS, RCMP, AAFC, Transport Canada, Health Canada, etc.), without counting the provinces and municipalities.

Not only that, but within Public Safety Canada, the branch that holds primary responsibilities for EM is the Emergency Management and Programs Branch:

You’ll see the DG for the Government Operations Centre (GOC) on the right. The GOC – where I used to work – is the primary coordination hub for EM in Canada. All the people on this organizational chart (and those not on it) are fantastic – hard at work to ensure our safety in Canada.

That said, while the GOC handles most of Canada’s EM and response/recovery coordination, the staff within Policy and Outreach and Programs hold primary responsibilities for planning new policies and efforts for mitigation, including regional offices. This creates some innate bureaucracy, as the individuals who are often working on responding to incidents (GOC) have limited crossover (relative to what they probably should have) with those who plan programs for preparedness and recovery. But yet, the GOC has a team of planners that plan for incidents and events.

The GOC

Public Safety Canada’s Government Operations Centre has a budget of approximately $11 million (CAD) and 112 full-time positions.

As this recent article illustrates:

Before COVID-19, the centre would received five to 10 formal requests for federal assistance a year. The centre co-ordinated 24 requests for assistance in 2022-23 and 20 in 2023-24.

The record-setting wildfire season of 2023 prompted activation of the operations centre’s event team for seven months, leading to considerable overtime for employees and redirection of resources from emergency management planning and exercises, the memo says.

One thing that always got me about the GOC is… it’s a coordination hub. The GOC has limited authorities to make decisions, provide insight into resources and equipment available, procure equipment and services… despite being asked to do all of the above. Instead, decisions are made by senior leaders (often political decision-makers) in other departments, with equipment and services procured by Public Services and Procurement Canada (with emergency procurement capabilities), stockpiles maintained by different departments – such as Health Canada’s National Emergency Strategic Stockpile, and on-the-ground actions being taken by the Canadian Armed Forces… which is a whole other challenge.

Essentially, what I’m getting at is the same as Jack Lindsay did in The Conversation:

Despite these evolving challenges, our emergency management systems remain strongly rooted in civil defence practices developed during the Cold War. These systems are over-stressed by recent events and continue to be underfunded by provincial and federal governments.

The current emergency management system, designed around the division of roles, responsibilities and powers between federal and provincial governments, does not have a clear role for a national response agency.

Nor can the Canadian Armed Forces continue to be tasked as a routine solution. The resources required in times of disaster go beyond the traditional 911 emergency services to include utilities, private and not-for-profit agencies and a greater role for citizen involvement. But these resources are located in provinces and organized locally.

Emergency management therefore needs to be integrated into decision-making by all levels of government and communities to be effective.

Prof. Lindsay finishes that article by noting a response-focused national agency will not address any of these issues, which is why the GOC cannot simply be a separate agency on its own – the totality of EM must be integrated within the country, to ensure a clear delineation of roles and responsibilities throughout the entire life cycle of EM.

Making It Make Sense

I won’t attempt to tackle all of the above organizational charts or challenges that Canadian EM faces.

Instead, what I propose within this post is to remove the EMPB branch out of Public Safety Canada (PSC) and create an independent, arms-length federal agency (similar to CSIS) that the federal and provincial governments will fund to the level required to respond to the incidents we are seeing more of.

By removing EM from the general PSC branches into a separate agency, the Canadian EM agency can be better positioned to coordinate and direct actions that can save lives and costs on response(s).

PSC is presently responsible for Firearms, EM, National Security (CSIS, RCMP, CBSA), Cyber Security, and indigenous policing/Safety. That is a giant portfolio—and one that can quickly be overshadowed when the Minister’s and Deputy Minister’s attention is placed on emergencies and disasters.

The nice (or possibly terrifying) thing is that Canada can follow existing models for a Canadian EM agency.

Models

United States (Federal Emergency Management Agency)

Wooooo boy. FEMA is a doozy.

I won’t sit and pretend that FEMA is the be-all-end-all-perfect-encapsulation-of-EM-agencies – far from it. (See here, here, here, here, or pretty much any EM practitioner or disaster researcher’s Twitter/X account.)

However, FEMA is undoubtedly a model that Canada can look to. For one, FEMA has a significant budget—$30 billion USD. Second, FEMA can send individuals with proper resources and equipment to respond to events on the ground, reducing the necessity of having the armed forces (or National Guard) respond in that capacity. Third, FEMA conducts a significant amount of training throughout the U.S., standardizing practices and ensuring a common language and level of preparedness for practitioners.

That in lies the main benefit I see about FEMA – everything starts with FEMA. Have a question? FEMA. Need training? FEMA. Stockpiles? FEMA. Boots-on-the-ground? FEMA. Money for preparedness initiatives or recovery? FEMA. Whether that works effectively all the time or not, it certainly is more efficient than playing a game of “Who’s jurisdiction is it?” each time you need to answer one of those questions. While each state and most municipalities (looking at you, Buffalo, NY) have EM positions and agencies, they can also each look to FEMA standards and practices to guide their efforts. We cannot say much of the same in Canada, as we have yet to reckon with our slow progress within EM.

Personnel and Budget

FEMA has approximately 22,000 staff and a budget of $30 billion (USD). It falls within the US Department of Homeland Security (which can also be another criticism, with too much focus on security events and less on those incidents that EM primarily deals with).

Australia (National Emergency Management Agency)

Australia’s NEMA is an executive agency under the Department of Home Affairs, similar to our Public Safety Canada.

The Australian Government formed NEMA on Sept 1, 2022, combining the National Recovery and Resilience Agency and Emergency Management Australia.

NEMA is an interesting model for Canada to follow, as the responsibility would still fall to Public Safety Canada (the Home Affairs Department). It would bring together resiliency, preparedness, response, and recovery missions under one roof, with an independent budget, additional resources, and a clearer line of sight into responsibility and action.

The line of sight into responsibility and action is essential—based solely on the NEMA “coordinator-general” (the head of the agency) salary of over $320,000 (AUD), that position would be in alignment with a Deputy Minister of a Canadian federal government department and heads of other agencies (e.g., CSIS). The Canadian GOC’s head is a Director-General, closer to the $170-$200k/year mark.

As the Home Affairs website illustrates, NEMA was formed to “create a single end-to-end agency to respond to emergencies, help communities recover, and prepare Australia for future disasters.”

Personnel and Budget

NEMA has an average staff of 415 employees and an allocated resource budget of $400 million (AUD) in 2024-25. It’s important to note that these figures show a discrepancy from Canada as NEMA has responsibilities for some level of grant funding and preparedness stockpiles, which are shared throughout the Canadian governments (also another challenge!).

Challenges

However, as with Canada, Australia’s constitution primarily delegated responsibilities for emergency management to individual states, which then requested assistance as necessary.

Part III: Challenges and downsides

Let me get the elephant out of the room: we cannot (and should not) create a Canadian EM agency until we are able to update our legislation appropriately for modern incidents. We have great people and relatively okay processes, but without the legislation, budgetary resources, and political support, a Canadian EM agency will fade off into the sunset (or, more likely, be dragged out by the tide of the ocean).

The federal government needs to update the Emergencies Act. The federal and provincial governments need to standardize and better legislate (likely within the Emergencies Act) which responsibilities fall to each level of government. The federal government must find a way to reduce the need to request the armed forces to assist an area during a disaster (and I’m frankly not sure if all that responsibility should fall to a few non-profit organizations, as it is moving towards…).

There’s just too much going on. Ask any EM practitioner in Canada to explain the Canadian EM system—it’s a confusing mess of overlapping roles and unclear responsibilities, buoyed by funding for (incredible!) organizations that have no accountability to government or the public, no formal standardized training mechanisms throughout the country, and a lack of funding and political support for those who do the roles.

But what would be an emergency manager without a confusing mess of overlapping roles and unclear responsibilities?